It wasn’t long before I noticed something alien in my vagina. A node in the wall. Left side—my left—about half a finger in. My first thought was birth injury, though I’d had a C-section so that didn’t track. The node didn’t hurt, but it also didn’t heal. It seemed over time to harden. I did some research. A vaginal dermoid cyst, I decided, a condition so rare and unlikely I would never ask my doctors about it. They already thought me drug-seeking and insane.

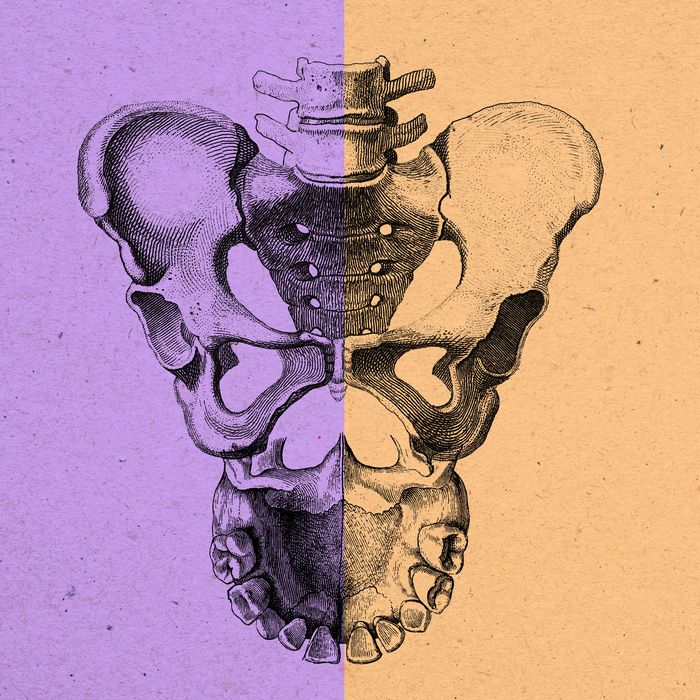

Cyst. Such a soft, sisterly word, all air. It allowed me to nearly forget the nub for months, until the day my daughter cut her first tooth. Absently letting her gum my index finger, I felt an edge and recoiled. I put my finger immediately back in her wanting mouth and found a spearhead of enamel. I thought: if this is tooth then that is tooth. More research revealed that vaginal dermoid cysts are in fact sometimes teeth. I found mine inside me that night and pressed it, confirming.

Naturally, at first I felt myself a mutant. I was afraid and disgusted. But most vaginal dermoid cysts are benign, I read. They come from DNA the baby leaves in you. I admit I did not entirely grasp the science. But rather than hate or fear the tooth, I resolved simply to monitor it. Observe without judgment, as the yogis advised. I ministered to the tooth. I fetched the green glass jar of olive oil and the ceramic fingerbowl Theo had used while stretching my perineum throughout the third trimester. It had been a source of great anxiety for me during pregnancy, the fate of my woefully inelastic perineum. My fear of episiotomy was right up there with fear of death and C-section, though it was the C-section that ultimately rendered my dutiful stretching regimen for naught.

I dipped my finger pad in the olive oil and stroked the tooth with the same forced fondness with which I applied ointment to my stretch marks, trying to practice the self-love encouraged by my therapists and budtenders. I deleted certain apps in hope of replacing the shocking image search results for birth+injury or vaginal+dermoid+cyst with the throbs of my own body.

Miraculously, it worked! The tooth was hard and unequivocal, but not unpleasant to touch. It did not at all interfere with masturbating, neither with digits nor with toys, and Theo and I were not really having sex at the time, so the tooth was truly no bother. Neither were the others, as, gradually and at about the same rate as my daughter, I cut a ring of them.

Tooth enamel is the hardest substance in the body, I read, understanding myself to be mythical and rare. Possibly it was my imagination (and what does it matter if it was? what is any of this—love especially—if not imagination?) but after my teeth came in, my orgasms became longer and stronger, more intense and easier to come by. I filled my alone time with them.

Yes, I said love. I loved the teeth and was unafraid of that love. I loved freely, as the poet advised. The teeth became my secret companion. I told no one, not Theo and, as I’ve said, not his colleagues tasked with evaluating what sort of risk I posed and to whom.

I did not want to hurt the baby or myself. I stressed this. We were the only people I didn’t want to hurt.

How long have you felt this way? was a question they all liked.

Since my baby was born. No, before. Way before. Since I was clouds pressed against a mountain. Since Tecopa.

I was okay. If I stopped breastfeeding and started meds and kept going to therapy and called my sister every day and journaled and beed a lizard at hot yoga four or more nights a week and took a lover or two, I would be okay—would survive my child’s first winter, a sludgy era of despair, bewilderment, and rage passed in the palm of the mitten.