163

President Donald Trump should stop hyperventilating about voter fraud and draft a gracious concession speech just as Richard Nixon did when he narrowly lost the 1960 presidential election to John F. Kennedy.

The goodwill generated by such a gesture will be sorely needed if Trump embarks on his next possible scheme, obtaining pardons for his friends, family and, most importantly, for himself. If he fails in this task, his future water view could be from a cell on Rikers Island rather than his Mar-a-Lago estate.

A presidential pardon is a kind of legal magic wand capable of providing complete immunity from all past and present federal crimes charged and even uncharged, depending upon the wording of the pardon. A full pardon essentially forgives a crime and eliminates all of the punishments, penalties and disabilities that flow from it. It does not provide immunity or forgiveness for future crimes. All 50 states have varying pardon procedures in their own laws.

In recent New York court filings, prosecutors from the Office of New York District Attorney Cyrus Vance and the Office of Attorney General Letitia James defended the service of subpoenas on the President and the Trump Organization, referring to news articles mentioning a variety of “schemes to defraud,” including possible insurance and tax fraud. This phraseology is familiar to white collar criminal defense attorneys who see such vocabulary frequently used in bank fraud investigations and indictments. (Trump has denied any wrongdoing.)

The President’s former personal attorney, Michael Cohen, in Congressional testimony last year, suggested that the President engaged in a business practice of inflating the value of property when making insurance claims and of exaggerating profits when seeking loans while exaggerating losses when filing tax returns.

A ProPublica report on Trump’s financial records and Cohen’s testimony quoted financial expert Ken Reardon’s observation that “It really feels like there’s two sets of books — it feels like a set of books for the tax guy and a set for the lender.”

Cohen has also directly accused the President of being his criminal co-conspirator in federal criminal campaign law violations involving the so-called “Stormy Daniels payoff,” for which Cohen was sentenced to three years in jail. If Cohen’s testimony is believed and if subpoenaed records not only corroborate him but reveal other damaging material, the President could be tied up for years in criminal and civil litigation. If convicted, such charges normally result in jail sentences as Cohen has personally experienced and discussed in graphic detail in his book, “Disloyal: A Memoir,” and in published interviews.

To protect himself from the possibility of prosecution when he leaves office, here are some ways the President might be able to obtain a pardon before he leaves office.

Strangely, the road map to these possible strategies was drafted in 1974 when Mary C. Lawton, an Assistant Attorney General in the Department of Justice at the time President Richard Nixon was under the spotlight in the Watergate scandal, was assigned the task of researching whether or not a president could pardon himself.

Lawton’s memorandum of law on the subject concluded that even though the wording of Constitution did not explicitly prohibit a presidential self-pardon, it was obvious to her that such a pardon would be wrong. While citing no legal precedent supporting her position, she relied on a bit of legal common sense stating: “Under the fundamental rule that no one may be a judge in his own case, the President cannot pardon himself.” Lawton then proposed two alternative approaches that Trump might consider when he accepts that his voter fraud lawsuits aren’t going to change the outcome of the election.

One of Lawton’s suggestions: that presidents could use the 25th Amendment to declare that they are temporarily unable to perform the duties of the presidency, causing the Vice President to become acting President. In that capacity the new acting president could then pardon the incapacitated president. Thereafter the president could either resign or resume the duties of his office.

If Lawton’s suggestion were to be applied to the current situation, President Trump would submit to the President Pro Tempore of the Senate a written notice of his inability to discharge the duties of the presidency. This would immediately allow Vice President Mike Pence to become acting president. Pence could then pardon Trump and whomever else Trump did not want to pardon personally. Trump could then resume the presidency or allow Pence to continue in office until the Inauguration of President Biden on January 20, 2021.

It may seem crazy, or perhaps suspicious, for the President to formally state that he is unfit for duty without a tangible reason, but according to the wording of the 25th Amendment, the President merely has to say in writing he is “unable to discharge the duties and powers of his office.” No medical exam and no reason needs to be given. Maybe Trump will be so distraught about the possibility of being indicted that he is legitimately too preoccupied to serve as president. Or perhaps he will simply want to claim inability to lead so that Pence may step in and pardon him. Either way, strange as it may seem, this strategy is constitutionally within bounds.

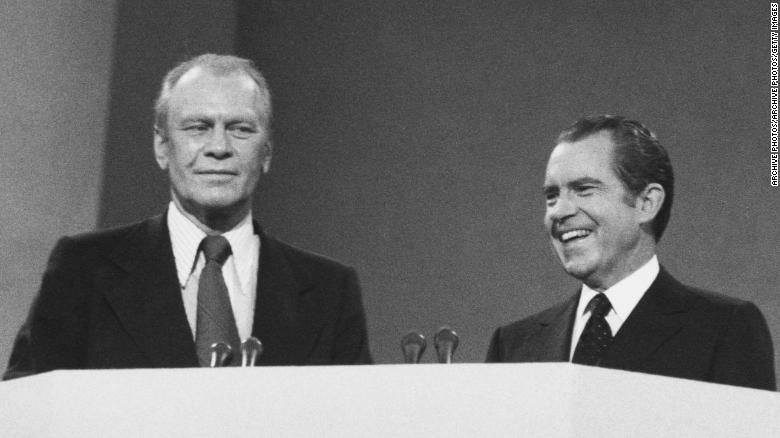

This scenario presents two problems for Trump: getting Pence to cooperate, and how to get a state pardon since federal pardons don’t cover non-federal crimes. Perhaps Pence could be persuaded that Trump’s fiercely loyal base would be grateful to him for saving the President from the vengeance of his political enemies. The Vice President might believe that such assistance could boost a future Pence presidential run. Of course, he would have to consider the public anger directed at Gerald Ford by both Democrats and Republicans after the Nixon pardon before making such a fateful decision.

Dealing with a potentially recalcitrant Pence and solving the state criminal liability problem might cause the President to take a serious look at another Lawton idea: a Congressional pardon.

In her memo, the ingenious Lawton suggested that it might be possible for Congress to enact special pardon legislation giving itself the power to pardon sitting presidents. This would not unconstitutionally usurp the presidential pardon power because, as Lawton previously opined, a president cannot legally pardon himself. Assuming Lawton’s legal reasoning is correct, the President need only convince House Speaker Nancy Pelosi to sponsor legislation authorizing a congressional pardon for him for all federal and local crimes. Just to be safe, Trump’s lawyers might also demand a New York State pardon as a hedge in case the doctrine of federalism bars Congress from forgiving state crimes.

That might seem unlikely, if not impossible, given the current vitriolic political climate. But perhaps Vice President Pence can be dispatched to try to convince Speaker Pelosi and New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo that it’s time for the country to move on without Trump fomenting chaos and discord as he fights criminal charges well into President Biden’s first term. If Trump really wants to make this deal happen, he might try offering Pelosi, Cuomo and the entire nation one additional document: A full confession of guilt to criminal conduct as president and a promise never to seek or hold public office again. Would it be legal? Who can say for sure? Would it be a deal that Democrats would take? It’s likely still a long shot. But, if Trump has taught America anything, it is this: Never write off a long shot.